ReEngineering the Hospital Discharge to Improve the Transition from Hospital to Home: An Overview and a Look to the Future

Authors Brian W. Jack, MD 1,2,4 Kirsten Austad MD, MPH 1,2,4 David Renfro RN 3 Suzanne Mitchell MD, MSc 5

Affiliations

1. Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, Boston University

2. Boston Medical Center, Boston, Massachusetts 3. Palo Alto VA Medical Center, Palo Alto, CA

4. Boston University Center for Health Systems Design and Implementation, Boston, Massacusetts

5. University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School, Worcester, Massachusetts

Patient Safety and Hospital Discharge

The Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) released To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System,1 as a seminal call to prioritize patient safety in November 1999. This report catalyzed care-delivery and policy improvement agendas. With leadership from the Agency for Health Quality and Research, the patient care transition from the hospital to home rapidly became a priority. Researchers subsequently reported a plethora of patient safety issues including challenges in consistently providing patients with information about their medicines, appointments, diagnoses and contingency plans if a problem arises. Such lapses result in patients correctly stating only about half of the instructions they receive.2, 3 Further, there are care gaps in monitoring pending tests4 and coordinating post-discharge tests.5 Higher rates of readmission among patients discharged on the weekend illustrate variability in care providing opportunities for improvement.6 It was no surprise when reports showed that nearly 20% of patients suffered an adverse event after hospital discharge, many of which were preventable or ameliorable.7 Half of patients take their medicines incorrectly after discharge and 30% have an adverse event related to medicines within 30 days.8 Those with communication deficits such a Limited English Proficiency (LEP) and those with low health literacy are more than two times more likely to suffer an adverse event.9 In this setting poor standardization and quality, Jencks et. al. reported in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2009 that 1 in 5 Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries are readmitted within 30 days of discharge, and only half of those readmitted patients have a post-discharge visit before readmission.10

Designing a Standardized, High Quality Discharge

In 2003, with funding from the AHRQ, our research group began work to better define the components of a high quality discharge. To do this, we adapted safety methodologies from other fields such as probabilistic risk, process mapping, failure mode effects analysis, and root cause analysis.6, 11 To do this, we brought together a group of nurses, physicians, pharmacists, health service researchers, and patients and used iterative group process meetings to identify potential failures at discharge, prioritize these failures, and brainstorm alternatives.

We created new process maps and delineation of roles and responsibilities, information flow among caregivers, and post-discharge reinforcement. The importance of language assistance for patients

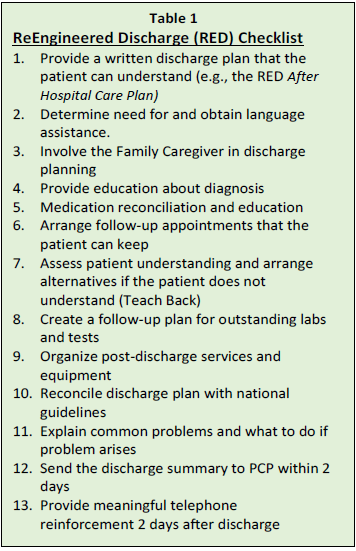

with limited English proficiency, and the important role of family caregivers in the discharge process were emphasized.12 Table 1 shows the checklist of activities that we consider essential components of a standardized, high quality discharge known as the “ReEngineered Discharge” or Project RED.

The paper first describing RED in the Journal of Patient Safety13 was this journals most cited in 2007.14 In 2009, we published an article focusing on the role of hospital case managers in improving the quality of the transition from hospital to home.15 This article is now the most cited article in the history of the journal Professional Case Management.14 In 2006, the National Quality Forum (NQF) updated the Safe Practices for Better Healthcare developed in 2003. The guideline was based on components of the RED program.16

Can a Comprehensive Discharge Process Reduce Rehospitalization?

In the mid-2000’s, intervention studies primarily focused on improving care in the post-discharge period17,18 and it was not known if improving the hospital discharge process would result in lower rates of rehospitalization.

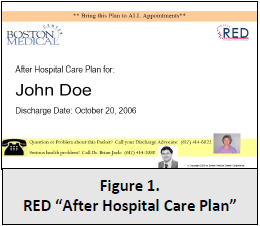

To test this hypothesis, we conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) with funding from the National Institutes of Health. A patient education tool called the “After Hospital Care Plan” (AHCP) operationalized the component of RED. The AHCP was designed to be understood by patients at all health literacy levels. It used large fonts, color, and icons to provide clear instruction about medicines and appointments color-coded to a calendar listing activities in the next 30 days (Figure 1).19 A research nurse collected information, created the AHCP, taught the patient the information contained in the document and confirmed understanding using the “teach-back” technique.20 A Doctor of Pharmacy conducted a post-discharge telephone call to reinforce discharge education and to correct problems.

In this study, we randomized 749 adult patients admitted to the general medical service at Boston Medical Center. The average age was 50 years, half were Black and receiving Medicaid, and 10 percent were homeless. The RED intervention reduced the combined outcome of 30 day all cause hospital readmission and emergency department visits by 30%. Intervention participants better understood their diagnosis, medicines and attended more follow-up appointments than controls. Overall, this trial showed that improving the quality of hospital discharge could lower rehospitalization rates in this urban safety-net population.21 The article describing this study has been cited nearly 2,000 times, and is described in the book 50 Studies Every Doctor Should Know.22

Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of Transitional Care

Subsequently considerable evidence has accumulated to confirm that transitional care interventions lowers hospital readmission. A meta-analysis of “interventions to improve communication at hospital discharge” now includes in 16,070 patients 60 RCTs showing a combined 31% lower readmission rate, 24% higher adherence to treatment and 41% higher patient satisfaction.23 A systematic review of 47 studies of interventions designed “to ease the care transition from hospital to home or to prevent problems after hospital discharge” concluded that the overall relative risk for hospital readmission was reduced by 23% and mortality reduced by 30%. There is now ample data to consider interventions like RED to be a best clinical practice at the time of hospital discharge, and to incentivize broad implementation efforts across the US.

Patient Safety Collides with Public Policy

As data became available showing that improved transitional care processes at hospital discharge can lower hospital readmission rates, the Centers for Medicare & and Medicaid Services (CMS) identified rehospitalization reduction as a leading driver of preventable health care cost. In 2009, in their landmark report, Jencks et al estimated the annual cost to Medicare of unplanned rehospitalization to be $17.4 billion.

Subsequently, in 2013 as part of President Obama’s Affordable Care Act, CMS implemented the Hospital Readmission Reduction Program (HRRP). This program created penalties for hospitals with high 30-day all-cause readmission rates for selected diagnoses starting with heart failure, pneumonia and acute myocardial infarction.

Over the years following the HRRP, the combined impact of the HRRP financial penalties and dissemination of readmission reduction protocols have resulted in lowering rehospitalization rates. In 2021, the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) reported that since 2008, heart failure patient readmission rates dropped from 24.8% to 20.5%, heart attack rates dropped from 19.7% to 15.5% and pneumonia decreased from 20% to 15.8%. The rates for non-targeted conditions (e.g. pneumonia, heart attack and heart failure) have also declined by 2.2 percent (from 15.3% to 13.1%).24 The total cost savings to CMS over the past five years amounted to $1.9 billion. Importantly, these gains are not associated with increase in harm.25

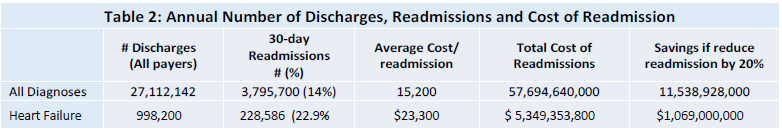

There are still important opportunities for continued cost saving. The most recently available data show there were 27 million hospital discharges and 3.8 million rehospitalization per year in the United States. With an average cost of $15,200 per admission, reducing rehospitalization by 20% would save $11.5 billion each year, with over 1 billion saved for those with heart failure diagnoses alone (Table 2).26

National Implementation Efforts

To support the HRRP, the CMS Innovations Center awarded funds to assist hospitals to formulate transitional care strategies aimed at reducing rehospitalization. The AHRQ commissioned the RED team to create a toolkit describing how to deliver each of the components of the RED program that could be used to support hospitals interested in reducing rehospitalization.27 The toolkit remains available at no cost on the AHRQ website and has been downloaded by hundreds of hospitals.28 For this work, Dr. Jack was named as one of the AHRQ grantees “whose work has led to significant changes in health care policy and notably influenced research and practice.”29 Table 2: Annual Number of Discharges, Readmissions and Cost of Readmission # Discharges (All payers) 30-day Readmissions # (%) Average Cost/ readmission Total Cost of Readmissions Savings if reduce readmission by 20% All Diagnoses 27,112,142 3,795,700 (14%) 15,200 57,694,640,000 11,538,928,000 Heart Failure 998,200 228,586 (22.9% $23,300 $ 5,349,353,800 $1,069,000,000

In the ensuing years, the RED team used the RED toolkit to train hospitals across the country as part the programs designed to expand the quality improvement demonstrations such as the Partnership for Patients (PfP) program, Hospital Engagement Networks (HENs) and the Quality Improvement Network-Quality Improvement Organizations (QIN-QIO).30

AHRQ and the Moore Foundation funded the RED team to study the implementation of RED in at 10 hospitals across the US,31 and in in five hospitals in California 32 to demonstrate the successes and challenges associated with RED implementation. Implementing hospitals were a mix of safety net, community, for-profit, and academic and non-academic institutions. This included an 8-hour in-person training and monthly learning collaborative phone calls.

Our article describing this work published in the Journal of Healthcare Quality31 received the Journal’s Impact Article of the Year Award recognizing “one article each year that has made a significant impact on healthcare quality.”

In 2013, the ReEngineered Discharge program won the Peter F. Drucker Award for Nonprofit Innovation and the $100,000 cash award in Vienna, Austria. The Drucker Foundation chose RED for this award because Peter Drucker believed that we should “addresses big problems with simple solutions”, and “addressing a multi-billion dollar problem by simply teaching people what to-do to take care of themselves when they go home from the hospital, is an idea that Peter Drucker would have liked.”

Case Study: Palo Alto Veterans Administration (VA) Hospital

There are notable successes among hospitals implementing RED. In 2011, the RED team conducted a 2-day training workshop at the Veteran’s Administration Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) in California. At that time, the 30-day readmission rate was high among the CMS targeted diagnoses. There was variability in the discharge process, and when asked on a post discharge phone call, 38% of discharged patients did not understand their medicines and 60% did not understand their discharge diagnosis. The hospital set a goal to standardize the discharge process using the RED tools.

The VAPAHCS team took a multidisciplinary and comprehensive approach that was nurse driven.33 The implementation team also aimed to implement all the components of RED with fidelity to the RED checklist. This approach is in accordance with new evidence showing implementing sites making use of more recommended care transition processes have higher rates of readmission reduction.34

The team faced pushback early in the implementation process including changed inter-professional dynamics, issues of accountability, fear about blame and bandwidth, and hesitancy about doing something new. Over 10 years the VAPAHCS team trained nearly all patient-facing acute care disciplines including 2,000 staff nurses trained in the RED “teach back” technique using videos the frontline staff created. RED has become the way VAPAHCS discharges every patient.

Table 3 shows the implementation strategies recommended by the VAPAHCS team.

Implementation Strategies Recommended by the VA Palo Alto Health Care System

1. Obtain hospital administrative commitment and visible support during the planning stage.

2. Create inter-professional implementation team to include an executive sponsor, external expert advisor, frontline leaders and staff, project coordinator, physician champion and patient and family caregiver representatives.

3. Provide formalized charge letter each member of the implementation team to emphasize the importance of the project and leadership support.

4. Empower the implementation team to implement and monitor each of the components of RED checklist, and create a reporting structure to assess accountability.

5. Hold regularly scheduled meetings that are process focused and data driven to “bust myths”, emphasize “good catches”, explore gaps, and celebrate wins.

6. Engaged frontline nursing and case management staff to have “fresh eyes” about integrating new processes within existing workflows.

7. Directly observe (e.g., GEMBA) the entire discharge process including observing doctors, nurses, pharmacists, social workers and patient/family education.

8. Review records of readmitted patients; and interview providers and family members to gain their perspectives on reasons for readmissions and to solicit potential fixes.

9. Established methods to monitor readmissions each day, and capture characteristics of readmitted patients to identify high-risk groups (e.g., patient age, diagnosis, hospital ward) to target in readmission reduction efforts. Share data transparently.

10. Empower frontline nurses to have the authority to pause a discharge for gaps in the process.

11. Assess social determinants of readmission (e.g., home status, caregiver support, living situation, food insecurity) and organize interventions to address (e.g., frequent follow-up visits, transportation) and provide needed equipment (e.g., scales, pill tracking, blood pressure cuffs).

12. Work with information technology to create an “After Hospital Care Plan” that is easy for nurses to create, is easy for the patient to read, and includes a calendar to assist with adherence to follow-up.

13. Train staff on the “teach back” technique to assess and document patient understanding.

14. Provide at least three post-discharge phone calls using a standardized script to reinforce the discharge plan and monitor recovery; take actions to fix problems identified.

15. Hardwire all interventions to prevent drift and create sustainability

Over time, VAPAHCS created an adaptive, collaborative, quality-focused hospital discharge culture and achieved great success. Over 10 years, they recorded a steady decrease in the rate rehospitalization among critical care patients from 50% to less than 5%. The VAPAHCS’s patient satisfaction scores rank first among high complexity VA hospitals. They confidence and skills developed by implementing RED have led to quality improvement in other areas, such as the creation of an End of Life Care Team with now over 300 interdisciplinary staff trained. The VAPAHCS has supported VA’s across the country to begin the RED program and now 15 VA’s use the VAPAHCS RED process.

Patient Centered Outcomes and Social Determinants of Health

As implementation efforts were underway, the RED team studied the aspects of transitional care that is important to patients. One study showed the positive impact of RED on patient experience scores, significantly increasing the percent of patients responding to the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) post-discharge survey

question “How well were instructions given about how to care for yourself at home.”35

As co-investigators in the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) funded “Project ACHIEVE” (Mark V. Williams, PI),36 the RED team contributed to a series of studies includiing summarizing transitional care components,37 identifying clusters of translational care components used in hospitals,38 and the importance of patient-centered approaches and trusting relationships. 39, 40 The RED team led a national study to identify the outcomes of transitional care important to patients and family caregivers.41

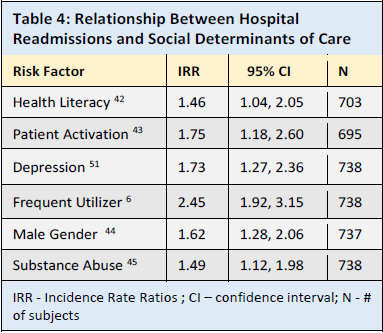

We also studied the relationship between social determinants of health and rehospitalization (Table 4). Using data from our studies, we showed that low health literacy,42 low patient activation,43 male gender,44 and substance use45 are associated with a higher 30-day hospital readmission. Using publically available data, we showed that a hospital’s rehospitalization rates are related to the number of family physicians practicing near a hospital,46, 47 and described increased rehospitalization rates among Medicare and Medicaid patients under age 65 with behavioral health disabilities (the “duel eligible” patient population).48

Our research also showed a relationship between the a high burden of depressive symptoms measured by the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and rehospitalization,49, 50 and that this relationship is “dose dependent.”51

This finding led our team to design an RCT to determine if clinical interventions after discharge will lower rehospitalization among hospitalized patients with depressive symptoms.52

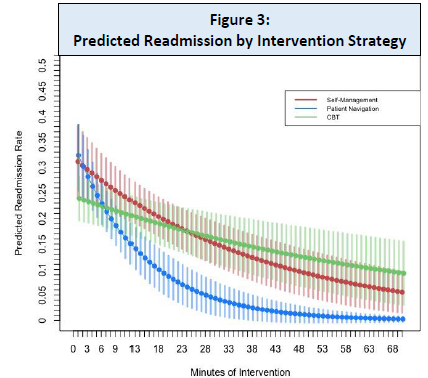

In this study, we randomized participants with PHQ-9 >10 with 356 receiving RED only and 353 receiving RED plus a 12-week post-discharge telehealth intervention that included cognitive behavioral therapy, patient navigation and self-management. At 90 days, 265 (75%) intervention participants received at least one counselling session. In the as-treated analysis, each additional RED-D session was associated with a decrease in 30- and 90-day readmissions. At 30 days, among 104 participants receiving three or more sessions there were 70% fewer readmissions. For the first time in transitions in care research, we were able to tease out the importance of each component of the intervention (cognitive behavioral therapy, patient navigation and self-management). Patient navigation was associated with the largest and most rapid decline in readmissions (Figure 3).

Connecting Hospital and Community Care: the Careggi-RED Program

Early post-discharge appointments to continue treatment and monitor recovery after hospital discharge is a key component of high quality transitions.53 About one-third of early readmissions (within 7 days) versus 23% of late readmissions (between 8-30 days) are preventable. Hospital interventions are better for preventing early readmissions,54 and making follow-up appointments is the most important strategy. Among patients discharged with follow-up appointments at 7 days, versus those without, the rehospitalization risk was 12.0 to 19.1 percent lower, depending on the risk level of patient, with higher risk patients benefitting more.55

Researchers at the Careggi Teaching Hospital in Florence, Italy created the “Careggi Re-Engineered Discharge” (CaRED) program in 2014 that is still ongoing. The program created a structured discharge protocol for more direct communication between hospital and community-based General Practitioners (GPs). Upon patient admission, GPs were authorized to access the teaching hospital electronic health record and able to contact hospital staff to discuss healthcare decisions. At discharge, GPs electronically received the “discharge letter” co-designed by the GPs and hospital doctors and designed to improve comprehensibility, readability, information completeness and handover clarity. The program improved perceived communication between GPs and hospital staff, improved the level of patient understanding of the reason for hospitalization, post-discharge therapy, follow-up care, and reduced the hospital readmission rates from 14.4% vs. 19.4 percent.

Barriers to RED Implementation: The Need to Save Nurses Time

Our implementation research clarified that while the RED RCT and subsequent research established efficacy (e.g., impact under RCT conditions), this did not always translate to effectiveness (e.g., impact under real world conditions.) It is common for interventions that are successful under RCT conditions to be less successful in real world conditions. Often high cost, time commitments, or workflow inconvenience leads to an intervention being less than optimally implemented (as it would be in a RCT). Only one in five interventions make it to routine clinical care, and the recent emphasis on implementation research has not reduced the 17 years it takes to implement new evidence-based processes.56, 57

From the various implementations of RED, we identified the challenges to successful implementation shown in Table 5.

Financial disincentives are an important barrier to implementing readmission reduction programs. Not surprisingly, hospitals participating in voluntary value-based reforms -- such Meaningful Use of Electronic Health Records, the Bundled Payment for Care Initiative episode-based payment program (BPCI), and Medicare's Pioneer and Shared Savings Accountable Care Organization (ACO) programs -- is associated with greater reductions in readmissions.58

It is also understandable that hospitals with value-based incentives are motivated to reduce rehospitalization as they benefit financially from reduced rehospitalization. This misalignment of hospital financial incentives in the current predominantly fee-for-service environment limits hospitals willingness to invest in additional staffing to improve discharge management. Without increased staffing for discharge activities, more duties are asked of nurses and case managers.

In this context, the main barrier to implementing RED is the challenge of adding new responsibilities and time commitments to already over-burdened hospital nurses and case managers.59 Widespread scaling of evidence-based readmission reduction programs such as RED requires workflow and staffing modifications that do not to add additional responsibilities to already overburdened staff.

Table 5. Barriers to Successful Implementation of RED 31, 32

1. Variations in fidelity to the RED components.

2. Not identifying who is responsible for each component of discharge planning and education.

3. Difficulty delivering RED components:

a. Making follow-up appointments

b. Completing medication reconciliation and teaching about medicines,

c. Completing meaningful and actionable post-discharge phone calls, and

d. Producing an After Hospital Care Plan

4. Insufficient nurse time allocated to discharge planning and education resulting from competing clinical priorities.

5. Ongoing misalignment of hospital incentives in a primarily fee-for-service hospital reimbursement environment resulting in financial pressure to fill beds.

6. Low priority by hospital administrators and staff who are unaware of research showing the impact that high quality discharges can have on clinical quality and reducing rehospitalization.

7. Gaps in communication among the inpatient team members and between the hospital team and post-discharge care.

8. Medications changed close to the time of discharge leaving insufficient time to teach and insure understanding of the discharge plan.

9. Integration with electronic records to ease the workload needed to create the discharge plan, particularly medicines.

10. Often relegating preparation of discharge documents to the least experienced members of the team (e.g., interns) who are most likely to make medical errors, and ineffectively communicate with post-discharge care providers and services.

Can Health IT Deliver RED and Save Nursing Time?

As these barriers to implementation became clear, it became a priority to identify ways to deliver RED efficiently in a way that saves nurses time.

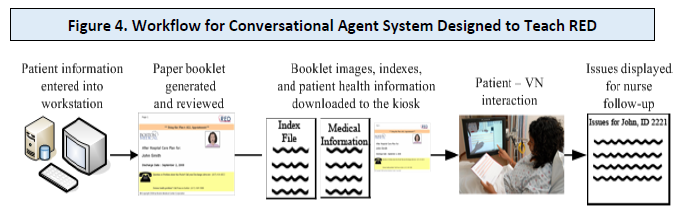

Conversational agents are computer-based animated characters designed to simulate face-to-face human interactions. Collaborating with colleague Timothy Bickmore, Professor at the Khoury College of Computer Sciences, Northeastern University, Boston, we designed a conversational agent system to teach the all the components of the RED to patients going home from the hospital.60 In this system, patients participate in individualized and tailored dialogue with “Louise” who addresses them by name, refers to their specific meds, appointments, doctor, etc., and creates “therapeutic alliance” using non-verbal communication such as empathy, gaze, posture, and gesture. Such systems are an effective medium to educate patients with limited health or computer literacy, as the human–computer interface relies only minimally on text comprehension, and prioritizes conversation making it more accessible to patients with limited literacy skills.61

Figure 4 shows the workflow of the “Louise” conversational system. Data is entered in the “workstation” and used to create the RED “After Hospital Care Plan”. The information also flows to the conversational agent software allowing the agent to teach this information in a back and forth conversational style.

The agent teaches the information while pointing to the information in the care plan on the screen. This is the same care plan the patient is holding. The agent confirms understanding using “teach back”, documents what was taught and patient understanding (or not). Health education is delivered with fidelity to best clinical practices to each patient, every time. Such systems save nursing time,62 can be used for longitudinal remote follow-up,63 and scaled for far-reaching impact.64

We enrolled 157 patients on the general medical service at Boston Medical Center to use Louise. Participants reported very high degrees of satisfaction, ease of use, and a sense of “caring” and understanding. Most importantly, when asked “Who would you like to receive discharge instructions from – a doctor/nurse or Louise, twice as many patients prefer Louise than a doctor or nurse, often reporting, “It was just like a nurse, actually better, because sometimes a nurse just gives you the paper and says ‘Here you go.’ Louise explains everything.” 65 The intervention lowered the hospital readmission rate from 16% to 12% compared to usual care.

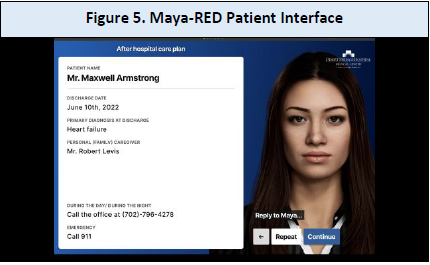

Introducing Maya-RED

Using the advanced technology available from MayaMD Inc. and the research results of the RED team, MayaRED is now available for hospital use as a commercial product (Figure 5). Maya’s advanced user interface, voice activation and natural language conversational capacity can now deliver personalized health education and post-discharge care as described by RED. Maya-RED prints a report at the end of the interaction documenting what the patient was taught and understands, exceeding CMS requirements for discharge education. Our analyses show that Maya-RED will saves more than 20 minutes of doctor and nursing time per discharge.

An important functionality of Maya-RED is that the system can deliver post-discharge reminders about appointments and medicines at times convenient to the patient, a functionality shown to reduce readmission.66 Patients can report any new symptoms and monitor their recovery. These interactions support patient learning at their own rate and pace (e.g., repeat, or pause the application, and re-review a module on demand), and allows family caregivers to learn about the care plan directly from Maya. The providers also have access to all the same patient information through MayaPro app that they can download on their phone for access to the patient data anywhere, anytime.

Selected chronic care patients also have access to the MayaMD Remote Patient Monitoring (RPM) system that can monitor a patient’ vital signs. RPM service provides reminders to take their readings of clinical measures using automated transmitting devices (e.g., blood pressure monitor, pulse oximeter, scale, and glucometer). The MayaMD Provider Portal displays the clinical measures, shows trends graphically, and notifies about any abnormal readings using individualized guidelines from the ordering provider. These telemonitoring activities also are also highly efficacious in lowering readmission rates.67

Conclusion

The hospital discharge is non-standardized and frequently marked with poor quality and is an important driver of health care costs. There is now ample evidence that improving communication at hospital discharge can prevent rehospitalization.

The ReEngineered Discharge successfully delivers high quality transitions in care, improve patient satisfaction, achieves patient-centered outcomes and reduces rehospitalization by over 20% -- while lowering health care costs. However, implementing these evidence-based processes into US hospitals requires smooth integration into customary hospital workflows, while not increasing health professional time needed to carry out these duties.

Now, rapidly evolving health-information technology systems using conversational agents such as Maya-RED have great potential to deliver the benefits of RED, with the added benefits of saving nurse and other health professional time, delivering post-discharge reinforcement of the care plan, and connecting chronic care patients to remote patient monitoring platforms.

About MayaMD

MayaMD Inc. was founded by Vipindas Chengat, MD FACP to reduce the prevalence of diagnosis and human cognitive error. MayaMD builds tools to quickly deliver the most relevant health and medical information to the consumer, patient, clinician and student so that diagnoses, treatment, learning and collaboration are timely, effective and affordable.

MayaMD believes that regardless of who you are or where you live or how much money you have, you should have rapid access to the best healthcare information and medical advice in the world.For more information about MayaMD and their MayaMD Health Assistant (for consumers and patients), MayaPRO (for clinicians), MayaEDU (for clinician students) and MayaMD Coronavirus (for everyone) apps, please visit www.mayamd.ai or the iTunes or Google Play app stores.